CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS ||| Ch.X. THE MEN

Category: Christopher ColumbusX

THE MEN

Any great undertaking, whether it is an expedition like Columbus’s or, for example, a war, needs three things.

First, it needs a courageous leader. The leader is the man with the Idea, the man who will fight for his Idea even though everyone else seems to be against him. Christopher Columbus was such a leader.

Secondly, equipment is needed — the products and inventions of other men. Without ships like the “Santa Maria”, the “Pinta” and the “Nina” the journey was impossible. Columbus needed (and he actually had these things!) the magnetic compass, the quadrant and the astrolabe —the navigating instruments which had been invented by that time. Of course, they were imperfect in Columbus’s time, but they were good enough to help make that great voyage. With these instruments, which measured the angles of the stars and planets, Columbus was able to tell his approximate position at almost any time.

It must be remembered that the idea of sailing westward round the earth had appeared almost a thousand years before Columbus. The ancient Greeks had tried to realize it but they were unable to do that with the ships and instruments they had.

But even the best of leaders and the finest of equipment are useless without the last and the most important element of a great enterprise — people. There must be people for the leader to lead. There must be people to use the equipment. No one makes history alone.

The men who went along with Columbus were of many different kinds. Their reasons for going were as varied as the men themselves. Some went because they loved adventure. Some went only because even greater danger awaited them at home.

For many, like the Pinzons, voyaging was a family matter.

The Pinzons had been the leading seafaring family of Palos for many generations. They were shipbuilders, navigators, merchants, seamen.

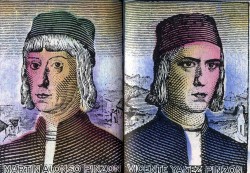

The eldest brother was Martin Alonso Pinzon. He was one of the most influential men in Palos. His help in organizing the expedition was great.

There was a reason for Martin’s generosity. It had long been his dream to travel the western sea route to the Indies. He burned with jealousy that the foreigner Columbus had been the first to get royal support for the journey he had always wanted to make. But more important to Martin Pinzon than his hatred of Columbus was his desire to go along on the trip.

Therefore, he forgot about his pride and did everything he could to help organize expedition. Perhaps if something happened to Columbus on the sea he would then be the leader of the voyage…

To be certain that he would control the situation at all times, Martin Pinzon brought his whole family into the enterprise. It was not hard for him to take command of the “Pinta” as its captain. He helped his youngest brother Francisco to be appointed master of the “Pinta” under his command. He also took on the “Pinta” his cousin Diego as mariner. But this was not enough, thanks to Martin his brother Vicente Yanez Pinzon became a member of the expedition as captain of the “Nina”.

The great voyage was also a family matter for the Nino family from the nearby town of Moguer. The Ninos were just as influential in their town as the Pinzons were in Palos. Juan Nino, who owned the “Nina”, sailed on it as its master. Another brother, Peralonso, became the pilot of the “Santa Maria”. The youngest of the family, Francisco, aged nineteen, sailed with his elder brother on the “Nina” as an ordinary seaman.

The men of the Nino family were not filled with hatred or jealousy for Columbus. They were loyal and honest, and Columbus was fortunate to have them with him. In time, Juan Nino became one of Columbus’s favourite shipmates and closest friends.

Most of the crew of the three ships were from Palos or nearby Moguer. Many of them had worked in the shipyards building the ships on which they now sailed. On the “Santa Maria”, a Galician vessel, there was of course a group of Galician sailors who were friends among themselves only and who scorned the “provincials” from Palos.

Even among the crew there were many family groups who were hostile to each other because of old quarrels.

Why did these men join the expedition? Many, of course, had little choice. Their families were hungry and any job was good for them. Some were threatened and made to go because they owed money to the Pinzons. The threat of debtors’ prison and hardship for their families was enough to bring some men aboard.

But surely many men went with the expedition because they wanted to be a part of the great adventure. Besides, Christopher Columbus promised that mountains of gold and rivers of jewels awaited them on the other side of the Ocean Sea.

Many other men came along on the trip because of Pedro Vasquez de la Frontera. Pedro Vasquez was an old weatherbeaten sailor of Palos.

Forty years before, in 1452, he had sailed on a voyage of exploration for the Prince Henry of Portugal. His ship had sailed westward over the Ocean Sea as far as a great mass of seaweed that stretched over the surface of the ocean farther than the eye could see. They entered this mass of weed, which they called the Sargasso Sea. The Ocean had no botton under this strange field of green. But, afraid at last, the captain had turned the ship round and ran for home, to the enormous disgust of Pedro Vasquez de la Frontera.

Since then Pedro Vasquez had believed that there was land just a few miles beyond the Sargasso Sea, and for forty years he had waited for a mariner brave enough to attempt the voyage again.

So now he stood in the market-place of Palos shouting to the group of younger seamen who gathered round him, “Sign up with Captain Columbus! Sign up for glory, for Spain, for riches! If I were twenty years younger, nothing on earth could keep me from going along, too. I tell you that with my own eyes I have seen mountain peaks to the west, out there on the other side of the Ocean Sea!”.

There was no better recruiting officer than Pedro Vasquez de la Frontera. He was very sorry that he was too old to sail himself.

Others, like Bartolome de Torres, needed no urging. Some years before, the hot-blooded Bartolome had quarrelled with another man and, when the quarrel was finished, the man lay dead on the ground and Bartolome stood over him with a knife in his hand. He was sent to gaol and sentenced to death.

But Bartolome had three friends who one night attacked the little town gaol and helped him to escape. The four comrades fled to the hills.

The three who had helped Bartolome to escape were also sentenced to death. For months they lived in the hills, hiding from the royal police. At last they heard about Columbus’s voyage and the royal decree that promised any criminal full pardon if he agreed to sail on the expedition. The four friends came out of the hills one day and volunteered. All four were sent to the “Santa Maria” as able seamen.

Some persons who were not accustomed to ships and life at sea went along, too. Each ship carried an official appointed by the king and queen, whose job it was to enforce the royal laws. There were accountants and ambassadors to record all the events of the trip, take care of the money, and establish diplomatic relations with the rulers of the other side of the ocean.

Another person who was not a seaman, but sailed on the “Santa Maria” was Louis de Torres. Louis de Torres was a Jew who had saved himself from expulsion to Africa by becoming a Christian. He was taken along as an interpreter because of his knowledge of Hebrew and Arabic. The Spaniards thought that Arabic was the mother of all languages. If the Great Khan responded to no other tongue, he would surely be able to speak Arabic.

Or, if it happened that the Khan could not speak Arabic, a knowledge of Hebrew would be useful — for had not Marco Polo reported that there were Jews in the service of the Khan’s court?

These, then, were the men on whom Christopher Columbus was to depend on his voyage of discovery.

All the members of the expedition were paid money, but uniforms or clothing of any kind were not provided.

A few things, however, were part of the equipment of every seaman: each man had a waterproof cloak with a hood. And every sailor wore the traditional woollen cap which is still worn today by Spanish and Portuguese fishermen. The men went barefoot even in the coldest weather, they did not bathe and shave during a long voyage of this type.

The captain, of course, was first in rank on the ship. Then, as today, he was responsible for everything that took place aboard. Next to the captain came the master and then the pilot.

Each vessel also carried a surgeon to look after the sick.

These — captain, master, pilot, and specialists like surgeon — were ship’s officers, and their home on board was in the stern of the ship.

The rest of the crew lived close to the forecastle. Head man among them was the boatswain. He was the busiest man on board because it was his job to lead the seamen in carrying out the orders of the officers. He had to know everything about sailing.

The steward was an important man, too. He rationed out the water, wine, food and firewood. In his spare time he was head instructor for the group of cabin boys, teaching them their duties and the trade of seamen.

Other seamen had special duties. The men sailed with Columbus knew their jobs well because the sea had been a big part of their lives since the day they were born.

Now, on the day before sailing, all looked westward, towards the far horizon that would soon bring them adventure, hardship, glory and death.